Somehow I failed to put together a post for Short Story Month, but I’m hoping June 1 is within the grace period. 😉 Since short story collections rarely get the big publicity push, they are overlooked and almost never make the bestseller list. Many people refuse to even read them, having a strong preference for the longer form of the novel. All of that is a shame. I love telling people about great story collections, confident that these books will provide a memorable reading experience. So that’s what I’m going to do today. Let me know if you add any of these books to your TBR list and what you think when you read them.

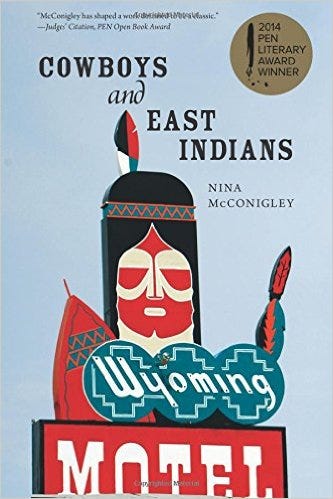

Imagine standing out by virtue of your appearance when you want to blend in. Or being invisible because of that same appearance when you want to be noticed. Nina McConigley explores this dual existence in the cleverly-titled Cowboys and East Indians, a collection of ten stories based on her experiences as an East Indian born and raised in Wyoming. Where most fiction exploring the immigrant experience is set in urban environments, McConigley takes us to the high altitude, windy isolation, and cozy cities of the least-populous state, a place most people would never expect to find Indian-Americans. McConigley explores characters’ attempts to navigate through their home and outside lives. She also shows us that Indian-Americans are not a monolithic group with uniform positions on religious, social, and political issues.

Heirlooms depicts the complicated lives of an extended family, starting in France in 1939 and ending in the American Midwest in 1989. In these beautifully written stories, characters struggle to survive the war and Holocaust, adapt to displacement and life as refugees and, later, immigrants to Israel and the United States. Each story packs a punch and the cumulative effect is both heartbreaking and inspirational. Hall writes with sensitivity and a clear-eyed insight about the issues of familial, community, and national loyalty and duty, as well as faith and forgiveness, and loss and survival. The cumulative effect of reading these stories is akin to completing a puzzle. Individual stories reveal specific issues and experiences, but when the entire puzzle is finished, the result is something larger and more memorable. The title story is especially heartbreaking. The narrator details what the family is leaving behind as they depart France for the U.S. Furniture, of course. Clothes, personal belongings and mementos – simply too much to bring. But also family members buried across France, their friends, their language, and even strong, flavorful cigarettes.

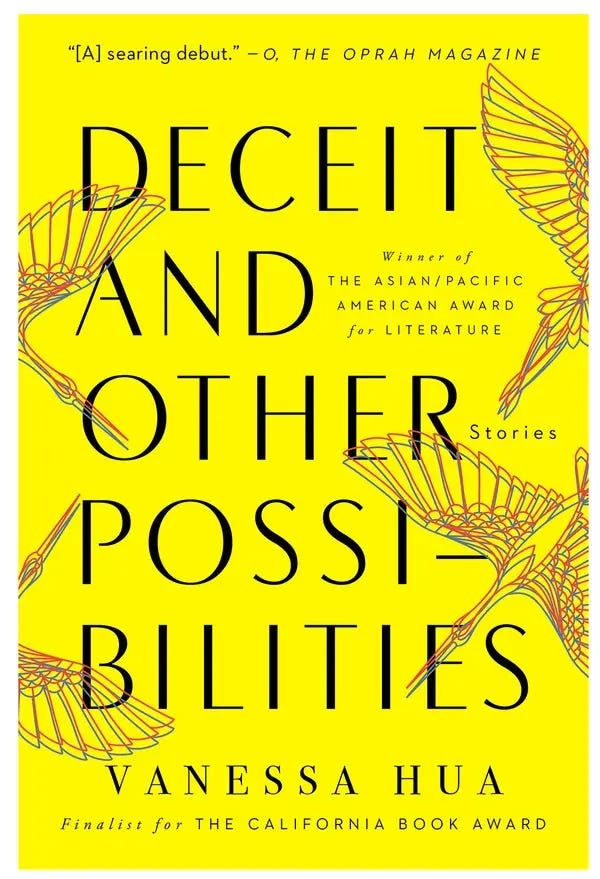

The 13 stories in Deceit and Other Possibilities concern characters struggling with their immigrant identity and resulting life choices: an elderly immigrant from Chinatown forced to return home after 50 years (“The Older the Ginger”); a Korean-American teen who finds an unusual way to become a student at Stanford in order to satisfy his ambitious parents (“Accepted”); a young Chinese-American celebrity from Hong Kong who returns to Oakland following a sex scandal (“Line, Please”); and a Korean-American pastor doing missionary work in East Africa whose intentions are not as good as they seem (“The Deal”). Hua is a masterful writer. Her stories feature a finely-honed sense of characterization, an ear for realistically quirky dialogue, and an acerbic tone that doesn’t completely hide her sympathy for these very human characters.

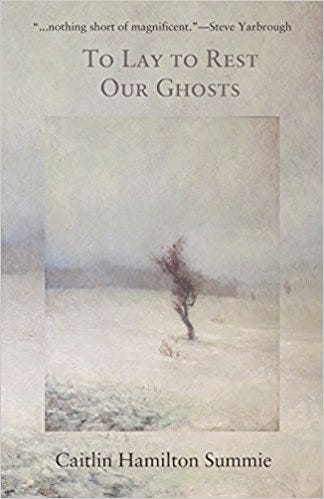

The characters in To Lay to Rest Our Ghosts are at crossroads of various kinds; they are struggling for emotional independence, attempting to resolve long-standing conflicts (usually familial), and trying to make sense of a complex and confusing world. These are quiet, intimate stories driven by character more than plot, yet they are compelling in both their dramatic tension and often unsettling (but not unsettled) resolution. Set mostly in rural and urban Minnesota, with detours to and New York City, these stories are probing examinations of the seemingly small, mundane moments that reverberate through our lives. Summie’s empathy for her characters’ humanity is so strong, and her prose so lovely, that a palpable warmth emanates from the stories despite their physically frigid settings.

Bobcat and Other Stories by Rebecca Lee is a brilliant debut collection that knocked my socks off. Lee’s stories are written with such observational precision and linguistic brilliance that they approach perfection. Her prose has an elegance and surface calm that slowly seduces the reader. Every sentence has a light touch, yet is fraught with consequence. Lee probes the dreams, delusions, hypocrisies, and endearing foibles of her characters with intriguing and often surprising results. Her stories rarely go where you expect them to, a bit like life itself. And Lee’s stories range far. They take place in New York City and New England, Montana and Saskatchewan (where Lee was raised), Chicago and rural Wisconsin, coastal Carolina and Hong Kong.

Each of the eight stories in The UnAmericans is a powerful, novelistic work that manages to encompass a character’s entire life through the use of representative experiences and telling details. Though the stories vary widely in terms of characters and settings, they share the ability to pull the reader in like a riptide and carry you away before you realize it. The title of the book refers to people who are, in fact, Americans, but are viewed as “un-American” in their beliefs, behavior, or sub-culture by the mainstream culture. Antopol’s stories display an impressive insight into the psyches of the various damaged characters, all of whom are trying to find their place in their own family, culture, or time.

Alex Poppe’s Jinwar and Other Stories is an unsparing look into the world of war in the Middle East, focusing on Syria and Kurdistan (Northern Iraq). The title novella and five accompanying stories take readers behind the scenes of the news reporting that has created the images we have about the people, places, and politics that have dominated foreign affairs for two decades. These are gritty, closely observed depictions of women in the midst of the chaotic world of war and post-war situations, with countries working at cross-purposes both military and diplomatic, and NGOs attempting to alleviate the suffering and facing obstacles from every direction. In short, it is hellish. Poppe balances the struggles of her characters with lots of gallows humor to leaven the brutality and senseless actions of a long list of military, rebel, and jihadist groups (primarily ISIS), all of which are oppressively patriarchal.

Violet Kupersmith is the daughter of a boat refugee from Da Nang and an American father, who met in Houston, where many Vietnamese were resettled in the 1970s. Her bicultural upbringing eventually led Kupersmith, while a student at Mount Holyoke College, to begin writing stories about the experiences of her mother and grandmother, and the folk tales the latter told her. In The Frangipani Hotel, she has managed the impressive feat of seamlessly blending these timeless Vietnamese folk tales with a contemporary approach to storytelling. The result is eight stories that seem simultaneously ancient and modern. Although the stories are always intriguing, the collection’s strengths are its mood and voice. Kupersmith manages to maintain a sense of mystery and foreboding throughout the book’s 240 pages, holding the reader’s interest with stories that explore the parallel worlds of the real and the supernatural, and the frequent occasions on which they intersect. Whether set in the streets of Saigon and Hanoi — crowded with a cacophony of people, scents, and sounds — or the fecund Vietnamese countryside, these stories are sticky with the oppressive heat and humidity of Southeast Asia. But Kupersmith’s greatest gift is her facility with the voices of all these characters, young and old, Vietnamese and American, as they tell their stories within her stories.

Although several novels and story collections have been written about the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Siobhan Fallon’s 2011 collection, You Know When the Men Are Gone, stands out. It is the only book that focuses on those left behind to wait at home: the wives, children, family members, and friends. Fallon, who is married to an Army officer, lived on the army base at Fort Hood, Texas while her husband served two tours of duty in Iraq. She became fascinated with the lives of the women on the base and the culture of coping created by those in the “rear detachment.” The eight interconnected stories here offer readers some insight into the many challenges faced by civilians who have married into the military life. Fallon focuses her attention on wives who are trying to get on with their lives despite their loneliness and anxiety about their spouses in the Middle East, the burdens of child-rearing, worries about family finances (always tight), and frequent moves to new bases in strange places. Her personal experiences inform these powerful stories with a realism that makes them feel almost like non-fiction. Fallon’s stories are so readable because she perfectly balances her character studies with compelling plots.

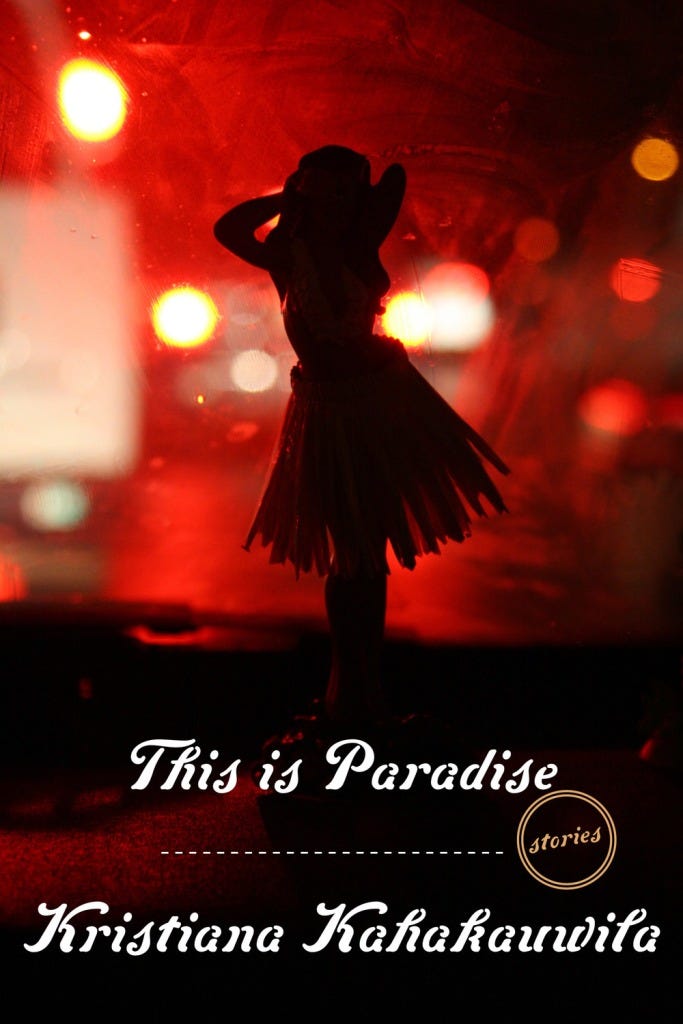

The stories in Kristiana Kahakauwila’s debut collection depict the real Hawai’i. Beyond the tourist images and fantasies of Hawai’i lies a real place, where island residents live and love, dream and die, and struggle desperately against economic, cultural, and ethnic forces beyond their control. These six stories are suffused with a bittersweet sadness for what could have — or should have — been, for words unsaid, emotions unexpressed, and customs misunderstood. Kahakauwila is the daughter of a Hawaiian father and German-Norwegian (American) mother and grew up in Long Beach, California. She made frequent trips to Hawaii (mostly to Maui) to visit family and was thus occasionally immersed in the local culture, but she was essentially a Southern California girl. Her ethnic and cultural heritage positions her ideally to write about the two Hawai’is, the tourist version and the locals’ version, with both objectivity and sensitivity, as well as insight and compassion.

I recommend Heirlooms every chance I have. Thanks for your recommendations. I've heard good things about the Ostlund and Sittenfeld books (no surprise) and just saw something about Amy Stuber today.

Thanks for including Heirlooms here with a number of my favorites! I recommend these collections, which I've just read: Amy Stuber's Sad Grownups, Lori Oslund's Are You Happy? and Curtis Sittenfeld's Show Don't Tell. All brilliant collections which show the genres range and beauty.