Guest author Marty Ross-Dolen: The Story of Telling My Story

In 1960, my grandparents were killed in an airline collision in the skies over New York City. They were traveling from Ohio to seek placement of their magazine, Highlights for Children, on newsstands.

In December 1960, my grandparents were killed in an airline collision in the blustery skies over New York City. My mother was fourteen at the time, and her parents were traveling from Columbus, Ohio, to seek placement of their family’s iconic magazine, Highlights for Children, on the newsstands. I was born six years later to a mother suffering from protracted mourning.

I knew very little about this life-defining tragedy while I was growing up. I knew that my mother was suffering, and I did all I could to contain her grief by limiting the questions I would ask and steering her onto other topics when she became sad. Yet I always wanted to know more. I was named for my maternal grandmother, and while I struggled to understand her untimely death when she was thirty-eight, I also yearned to connect with the woman she was, staring at her image in framed photographs and imagining what her life would have been like had she lived longer.

My mother became the archivist at Highlights for Children, Inc., a company which is now nearly eighty years old, still family-owned, and still delivering colorful magazines each month to the mailboxes of its happy young readers. About ten years ago, while clearing through decades of saved company and family artifacts stored in attics and warehouses, I asked her to collect any of her mother’s personal letters that she found and send them to me. I wanted to get to know my grandmother through her own voice. Soon enough, I was filling large plastic bins in my basement with precious words on aged stationary, letters written in her handwriting, paper she had once held. I would occasionally sift through them, developing in my head the possibility of one day telling my grandmother’s story through this treasure trove of materials, but mostly they sat idle. The sheer volume of pages felt too overwhelming to tackle.

I had another writing challenge that had been weighing on me as well. In December 2010, after a few years of researching the airplane accident on the internet and uncovering details about the disaster I had not been privy to as I was growing up, I learned of a fiftieth anniversary memorial event that was taking place to remember the accident’s victims at a cemetery in Brooklyn. I decided to attend the memorial, which turned out to be a profound experience, a connection with a group of strangers who held the same fifty years of grief in their hearts, each bringing their own unique story to this combined remembrance.

Seven months after attending the memorial, I wrote an essay about my day in Brooklyn, which included backstory about the accident, and I presented this essay in a writing workshop at The Ohio State University. I was struggling with the piece, because I knew that the writing only brushed the surface of my story, that it focused more on the memorial event than on the forty-plus years I had been trying to protect my mother from her complicated grief and at the same time containing my own. In discussing the essay privately with my professor at the end of the semester, he confirmed my suspicion that my work was not yet complete. He told me he thought what I needed to do was write a book.

I remember a sinking feeling when he said those words. I wanted to be done telling this story. I wanted to pack up the essay and check it off my list of painful personal life topics I had resolved through writing. Moving through the fiftieth anniversary memorial experience had been emotionally exhausting on its own, and then writing about it, though cathartic, had also taken a lot out of me. Now I was being told that my story could not be tied up with a bow as an essay. It was much messier than that, needed deeper excavation, required far more from me. It was a project that deserved my undivided attention.

So what did I do with my essay? I took the tall pile of printed copies filled with handwritten marginalia and extensive feedback from my fellow workshop participants as well as the members of my monthly writing group, and I promptly stuffed it in a cabinet, where it slept for nine long years.

I believe that the personal stories meant to be owned by greater humanity find their ways through us and out into the world. As much as I wanted to silence the essay that was stifled by the enclosed cabinet, I could hear it knocking on the back of the cabinet door. Many times I contemplated shredding the paper pile of precious feedback, but the urge was overcome by the gnawing feeling of knowing that I would need to write that book one day whether I wanted to or not. When my grandmother’s letters started accumulating in my basement, it was only a matter of time before I tackled the project.

That time came when the pandemic appeared. I had been contemplating pursuing an MFA in writing over the years, and the combination of extended time at home and the transition to remote learning made the option possible for me. I worked with wonderful faculty advisors who supported my determination to write the book I needed to write. I covered my dining room table with my grandmother’s letters and read one page at a time, absorbing her voice deeply enough to enter a place where I felt I could even converse with her, which I did, in my mind and in my writing. I returned to my childhood and found the places where trauma hid. I felt a shadow of grief hovering over many of my memories. I spent hours on the phone with my mother, recounting stories from her life and from mine. I sifted through what needed to be part of my book and what didn’t, what needed to be said and what didn’t, all with the goal of molding a book from words like clay, creating a container for the stories of three generations of women.

Sometimes ideas are meant to stew. Often writers have no control over when they will be ready to tell their stories. In my case, the circumstances needed to meld before I knew the time had arrived. Fourteen years after writing its foundational essay, my book has found its way into the world.

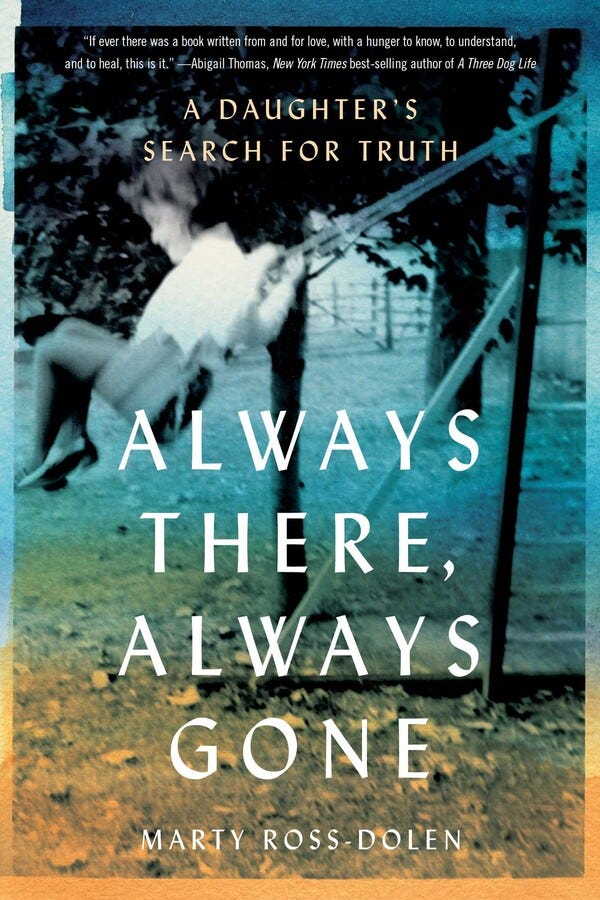

Marty Ross-Dolen is a graduate of Wellesley College and Albert Einstein College of Medicine and is a retired child and adolescent psychiatrist. She holds an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Prior to her time at VCFA, she participated in graduate-level workshops at The Ohio State University. Her essays have appeared in North Dakota Quarterly, Redivider, Lilith, Willow Review, and the Brevity Blog, among others. Her essay entitled “Diphtheria” was named a notable essay in The Best American Essays series. Her memoir, Always There, Always Gone: A Daughter’s Search for Truth was published by She Writes Press on May 6, 2025. She teaches writing and lives in Columbus, Ohio. Learn more at http://www.martyrossdolen.com.