Four more standout back catalog books you need to read

The third and final installment of my posts on backlist books that deserve your attention

In the third and final installment on backlist books that deserve your attention, I recommend four books from 2012, 2014, and 2016 that I don’t see mentioned anywhere these days. They were published in the early days of Instagram (and the Bookstagram community) and long before TikTok (and BookTok). So there’s a very good chance you haven’t heard of them (except, perhaps, for Laline Paull’s The Bees, thanks to the success of her most recent book, Pod). I found these four books (three novels and one short story collection) to be completely absorbing and thought-provoking works. If you’ve read any of them, let me know what you thought. And if this post leads you to read any of them, I’d love to hear about your reading experience.

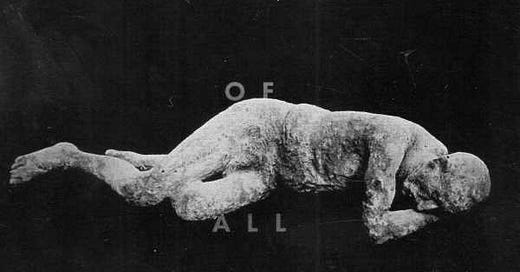

Oklahoma writer Rilla Askew deserves high praise for managing to explore the lives of those on both sides of the immigration issue without turning it into a one-sided screed. While Askew’s position is clear, Kind of Kin uses multiple narratives to put us inside the kaleidoscope of immigration politics at the national, state, and local levels.

The novel’s protagonist is Georgia “Sweet” Kirkendall. Her father, Bob Brown, a taciturn but respected local mainstay in the tiny town of Cedar, Oklahoma, has been arrested for harboring illegal aliens in his barn, to the surprise and disappointment of friends and family. What inspired this change so late in life? His parentless grandson, 10-year-old Dustin, is forced to stay with Sweet, who is already struggling with her own son, a young bully named Carl Albert, and her husband, who works long hours out of town and has grown emotionally distant from Sweet and Carl Albert. At the same time, Luis Celayo has entered the U.S. illegally to search for his long-lost sons, who went north to work. The plot is enriched considerably by the fact that Sweet’s niece, Misty, is married to an illegal alien who has been deported but has made his way back into the country. Then Dustin disappears, and the hunt for him drives the story to its dramatic conclusion.

On the other side of the legal and social divide are three less sympathetic characters. Oklahoma state senator Monica Moorhouse is a political opportunist who sees a harsh anti-immigrant bill as her ticket to national notoriety and Congress. Local sheriff Arvin Holloway is a blustery Joe Arpaio-inspired lawman who has never met a camera or microphone he didn’t like. Logan Morgan is a young TV reporter looking for a big story and a move to a larger market. They all have their own agendas, which involve little concern for the effects of such a law — or their actions — on real people’s lives.

While on paper the plot may sound melodramatic, it does not read that way. Instead, it comes across as a realistic depiction of the many lives affected by the political decisions made on the issue of immigration and immigrants’ rights. The narrative is fast-moving, the various viewpoints are woven together smoothly and logically, and the characters act like real people, not cardboard cut-outs intended to stand in for points in a political or legal argument.

One of the great joys of reading authors with whom one is unfamiliar is discovering a truly distinctive writer whose work pushes all your buttons, intellectually and emotionally. Amina Gautier’s The Loss of All Lost Things is just such a book. Her debut collection of stories, At-Risk (2012), won the Flannery O’Connor Prize for Short Fiction. The follow-up, 2014’s Now We Will Be Happy, won the Prairie Schooner Book Prize in Fiction.

Her third collection, The Loss of All Lost Things, is her most accomplished work. Here she moves beyond the concerns of her earlier work to the issue of loss in its many forms. Her characters have either suffered a loss, literally lost someone or something, or are at loose ends in figuring out what to do with their lives following a significant and often unexpected event. What so impresses me about these stories is Gautier’s ability to plumb the psyche of very complex characters with a psychological acuity that will break your heart repeatedly.

The opening “Lost and Found” follows a young boy who has been abducted by a man identified only as “Thisman” as they move from motel to motel over a period of several months. The title story takes us into the home and life of the grieving parents of the boy from “Lost and Found.” “Intersections” explores the seemingly cliched affair between a white college professor and a beautiful and brilliant black student with results that manage to sidestep those cliches. In “What’s Best for You,” we meet Bernice, a black single mother who works in the university library and is lonely but maintaining her standards. When the amiable new custodian flirts with her, she is forced to confront the cost of her biases.

The Loss of All Lost Things is a dark and often disturbing collection, but Gautier is such a gifted storyteller, the characters and conflicts so compelling, the telling details so perfectly chosen, that you can’t turn away. Amina Gautier is a fearless writer who I am willing to follow anywhere.

Rene Steinke’s Friendswood explores two issues that are seemingly discrete but are actually intertwined: corporate polluters turning a residential neighborhood into a toxic waste site and sexual abuse by high school athletes in a small town that worships football. In both cases, the immoral and possibly illegal behavior of privileged actors is indulged by the majority, who value economic growth and athletic prowess over questioning their way of life, the choices they make, and the cost of both.

The narrative is shared by four characters. Lee is a mother turned single-minded environmental activist when her teenage daughter Jess dies from a strange cancer. Jess’s life revolves around her part-time job in a doctor’s office and monitoring the adjacent property, the site of a former refinery. When she discovers that the site is belching toxins from the soil again, Lee moves from vigilant to vigilante.

Hal is a former mediocre high school athlete struggling to make a living in real estate; he is living vicariously through the athletic exploits of his son, Cully, and hoping that a recent religious rebirth will save him, his business, and his wilting marriage. Willa is a 15-year-old student with an artistic streak and an eccentric persona that doesn’t fit easily into the culture of this small town located between Houston and the Gulf. Dex is a classmate of Willa and Cully with more on his mind than just football and girls. Their lives intersect in ways they could not predict.

The two plot strands overlap in the sense that each involves predators steadily moving toward their distracted prey, while one good-hearted person attempts to intervene to save them. Steinke has written a book with engaging characters who are trying to achieve their goals; occasionally they come across as somewhat stereotyped but not to the extent that it undermines the story or its message. Steinke grew up in the actual Friendswood, Texas, and she knows small towns and their residents well; she knows that football, religion, and the oil business are often the Holy Trinity in such places.

Laline Paull came to the attention of readers worldwide when her latest novel, Pod, was a finalist for the 2023 Women’s Prize for Fiction. But my favorite of Paull’s three novels is her debut, The Bees. It combines the best traits of a thriller, a character study, a hero’s quest, and a dystopian fantasy to powerful effect.

Just as Richard Adams made readers care deeply about a warren of rabbits in his 1973 classic, Watership Down, Laline Paull’s The Bees will have readers worrying about the many threats, both external and internal, to the members of one hive in an English orchard.

Flora 717 is a dutiful member of the sanitation workers, the lowest caste in the hive, when it is discovered that she can speak (the “flora kin” group is mute). She draws the attention of Sister Sage, one of the priestesses that manage the hive for the Queen. Before long, she is promoted to the Royal Nursery, caring for the Queen’s newborns. Sister Sage realizes that Flora 717 is a rare bee indeed and determines to maintain a close watch over her, using her for the benefit of the hive but wary of her capabilities.

Flora is deeply conflicted between her genetic predisposition to “Accept, Obey, and Serve” (the workers’ mantra) and her rational and critical mind, which causes her to question, disobey, and ultimately lead. As she demonstrates her intelligence, bravery, and devotion to the Queen, she moves up literally and figuratively in the world of the hive. But her proximity to the Queen, the Priestesses, and the drones makes her privy to knowledge she would be better off not knowing. Before long, Flora has become a threat to the Queen in a way she could never have imagined.

Beyond its intense and exciting plot, The Bees is distinguished by its well-drawn and credible characters. Paull has plausibly imagined the bees’ views of the outside world with its many creatures, humans, and man-made structures. The novel’s other noteworthy accomplishment is the way Paull has seamlessly incorporated a wealth of fascinating information about bees without bogging down the narrative. Laline Paull’s background in screenwriting has resulted in a cinematic thriller with several scenes you are unlikely to forget.