Celebrate "Women in Translation Month" by reading these six outstanding novels

Pt. 1 features books from France, Italy, Sweden and Denmark. Pt. 2 will feature Asian, African, and Latin American authors.

I started this blog in 2013 when I realized that about a third to a half of my reading was literary fiction by women. I thought I might be able to offer a different perspective if I increased that percentage to 50-75 percent and only wrote about books by women. Before long, a huge majority of my reading was books by women; over the past decade it has remained in the 80 to 85 percent range. I’m thankful I made that decision 11 summers ago; reading these books has been intellectually and emotionally enriching.

One unexpected benefit of starting a blog with the intention of promoting literary fiction (and the occasional memoir) by women was my exposure to books in translation. I’ve gone from reading almost nothing in translation to regularly reading works from around the world (I’d estimate it at around 20 percent of my reading). Discovering Europa Editions, Other Press, and Graywolf Press made a huge impact in this regard. While many other indie presses publish works in translation, they make up the bulk of the books issued by these two publishers. I hate to think about all the great novels I would have missed if I hadn’t taken this journey in my reading. While translated fiction occasionally makes the bestseller list or at least catches on with readers of literary fiction (e.g., Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Quartet), most of these books remain below the radar, counting on word of mouth to reach appreciative readers.

Since August is Women in Translation Month, I thought I’d share some books that I loved and admired. In this installment, I feature two books from France, two from Italy, and one each from Sweden and Denmark. In the next installment, I’ll cover books from Asia, Africa, and Latin America. I hope you discover a few good books today.

Fresh Water for Flowers by Valerie Perrin

Translated from the French by Hildegard Serle

Europa Editions, July 2020

It might seem surprising that a book whose protagonist is a cemetery caretaker would contain everything life offers, but that’s the case with Fresh Water for Flowers, the second novel by French writer Valerie Perrin and the first to be translated into English. On first impression, this 474-page novel appears to be a charming and quirky story with a distinctly French sensibility.

It’s the story of Violette, a former foster youth working as a bartender who is swept off her feet by the older and magnetically appealing Philippe Toussaint. Before long, they are working for the railroad as level-crossing keepers; they live in a small house next to the tracks in rural France and only have to lower the barriers every few hours when a train passes by. Violette does the work while Philippe plays video games or goes on long rides on his motorcycle.

The core of the story concerns the shocking events in 1993-1996 that led Violette to the cemetery caretaker position, which she maintains for the next 20 years. Along the way we meet Sasha, the older gentleman who held the caretaker position before Violette and who serves as something of a surrogate father figure; the small group of men who work at the cemetery and often gather in Violette’s small house on the grounds for coffee and the desserts she bakes for them; and Julien Seul, a detective from Marseilles who comes to the cemetery to place his mother’s ashes, befriends Violette, and ends up revealing a mystery concerning a lawyer who is buried there. There is far more to everyone than meets the eye.

The story is heartbreakingly dark in one subplot in which Perrin displays great skill as a writer of mystery and suspense. Another subplot concerns the reasons behind the request of Seul’s mother that her ashes to be placed on the grave of a man Seul has never heard of. Perrin keeps the reader off-balance as she weaves these seemingly unconnected strands together into a life-encompassing whole. And all the while we root for Violette to build the life she deserves and experience the love she has been so long denied.

So this novel set mostly in a cemetery is in fact entirely concerned with life. Yes, there is loss, but there is also love and longing, passion and pain, heartbreak and healing. Fresh Water for Flowers is a completely engrossing reading experience.

The Missing Word by Concita De Gregorio

Translated from the Italian by Clarissa Botsford

Europa Editions, July 2022

Irina is an Italian lawyer living in Switzerland with her husband Mathias and their two daughters, Alessia and Livia. Their marriage ends after years of tension, and they maintain a relatively cordial relationship for the benefit of the girls. But one weekend Mathias fails to bring the girls back. They’ve disappeared. Then Mathias’s body is found, an apparent suicide. But where are the girls? Dead, lost, hidden?

In The Missing Word, journalist and broadcaster Concita De Gregorio imagines Irina’s life following this traumatic event. In a fragmented first-person narrative, De Gregorio puts us in the mind of a mother bereft of her children and relentlessly searching for them. She examines everything and everyone in an attempt to stitch together an explanation and find the girls, even if, as she eventually concedes, they are dead.

There are letters to her husband, friend, therapist, and grandmother, as well as to the girls’ teacher, a prosecutor, and a judge (asking her to review the inconclusive investigation). In short chapters, Irina writes psychologically revealing lists titled “Anger,” “Happiness,” “Words,” and “Memory.” But the heart of the story is contained in chapters focusing on episodes past and present involving Mathias, the nanny, Irina’s mother-in-law, her brother and father, and her new boyfriend, Luis.

The Missing Word is a riveting and heartbreaking exploration of parental love, memory, and the saving grace of words. But the missing word is one that describes a mother who has lost her children.

Meeting in Positano by Goliarda Sapienza

Translated from the Italian by Brian Robert Moore

Other Press, May 2021

Goliarda Sapienza may be virtually unknown to Americans, but in Italy she was a famous stage and screen actress in the 1940s and 1950s who turned to writing autobiographical works and fiction in the 1960s. Sapienza worked with some of Italy’s most famous filmmakers and became part of the intellectual elite. She was shaped in part by her experiences during World War II. In 1943, at age 19, she took a break from her acting studies to join an anti-fascist brigade, and she remained an outspoken political activist throughout her career.

Unfortunately, her frank and unconventional writing found little success in her lifetime. Most of her work was published after her death in 1996. Meeting in Positano, written in 1984, was not published in Italy until 2015. Sapienza tells the story, based on her own experiences, of an unusual friendship with a mysterious young widow named Erica in the isolated town on the Amalfi Coast during the 1950s, before it became a famous getaway favored by celebrities. It is a tribute to a very specific time and place and to a particularly intense friendship with a woman who could not have been more different.

Erica, in her late 30s, is a wealthy, aristocratic widow, beautiful in an imperfect way, who is lonely and, as she admits, not good at making girlfriends. For Goliarda, it is platonic love at first sight, as she is utterly taken by Erica’s unique appearance and charisma. In fact, most of the residents of Positano–a charming, eccentric group of supporting characters–appear to be in love with her. But no one really knows much about her background.

Slowly, the two women, separated by nearly a decade in age, become “the sisters,” as some in the town start to call them. Meeting in Positano is both an intriguing dual character study of two unusual women and a love letter to a town that no longer exists in its charming 1950s incarnation, before new roads made it easier to reach. Goliarda describes Positano as “a place that was still isolated from the barbaric advances of products, merchandise, and urban madness.”

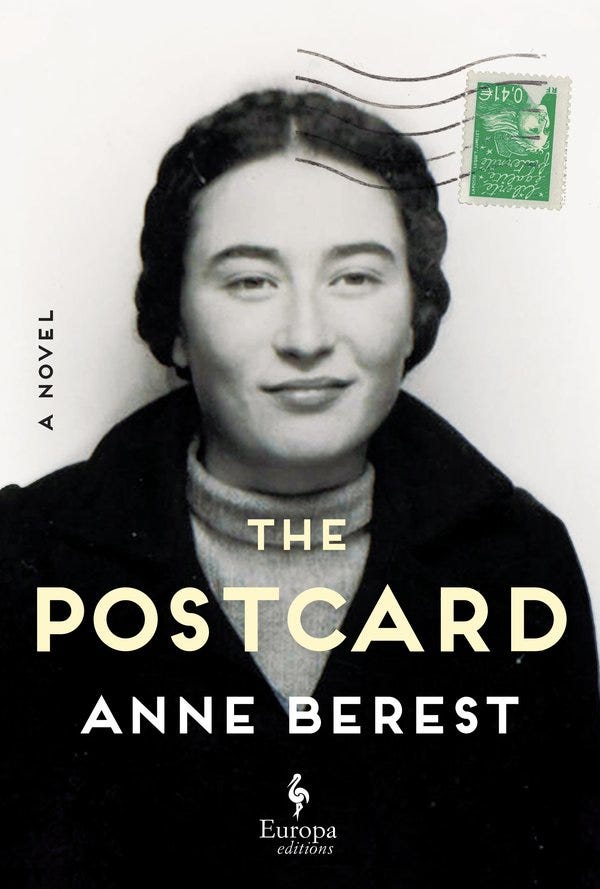

The Postcard by Anne Berest

Translated from the French by Tina Kover

Europa Editions, May 2023

In January 2003 a postcard arrived at the Paris home of writer Anne Berest’s parents. The only message: the names of her maternal great-grandparents and two of their children, all of whom had been murdered in the Holocaust. There is no return address and the handwriting is unusual. Who sent it and why, 60 years later?

In an attempt to discover the identity of the sender, Berest and her mother (the daughter of the oldest child, the only family member to survive the Holocaust) begin investigating the past to learn what happened to her great-grandparents and their children. (Berest’s surviving grandmother refused to talk about the Holocaust.)

The result of their search is this memoir/novel hybrid. It’s a history of the Rabinovitch family who fled Russia to Latvia after the Revolution, then emigrated to Palestine, and finally settled in France, where they were caught up in the Nazi genocide of Europe’s Jews. Berest also explores what life was like for Jews in Vichy France, at the societal and personal levels, with its collaborators and resisters.

The Postcard is also an examination of the effect of the Holocaust on one Jewish family’s descendants. Berest, a secular Jew, is compelled to examine her upbringing and reconsider her relationship to Judaism. And yes, she eventually learns who sent the postcard and why.

The Postcard is a riveting and heartbreaking read. I’ve thought about it a lot since I read it in late Spring, and I’m happy to say I’ve persuaded several people to read it. It was the clear choice for my favorite book of 2023.

Willful Disregard by Lena Andersson

Translated from the Swedish by Sarah Death

Other Press, Feb. 2016

Lena Andersson is a well-known newspaper columnist, social commentator, and novelist in Sweden. Willful Disregard, her fifth novel and winner of Sweden’s highest literary honor, the August Prize, was her first book to be published in the U.S., and it is an impressive introduction to a writer with keen insight into love in both its universal characteristics and its modern trappings.

Andersson probes the mind of thirty-one-year-old journalist Ester Nilsson, who becomes infatuated with artist Hugo Rask when she is asked to write an in-depth profile of the semi-legendary older man. From their first interview, they seem to be intellectual kindred spirits, and Ester is entranced. She is so convinced that her future lies with him that she leaves her long-term boyfriend. Undoubtedly, Ester reasons, Rask is disengaging from his other commitment as well. Ester hangs on Rask’s every word, gesture, and action, obsessively analyzing each for its true meaning with regard to his feelings and their burgeoning relationship. She squeezes impossibly rose-colored interpretations out of the most minor of words and deeds.

The ruthlessly unsentimental narrator sees through Ester’s pretensions and rationalizations into her true motives, flawed thinking, and overwhelming need to “only connect.” In doing so, Andersson has written one of the most accurate explorations of the self-deception and madness of new love that I have ever read. But Andersson also displays a sharp wit and the ability to find the bittersweet humor in most situations. Although Andersson never introduces Ester’s friends individually, she makes effective and drily humorous use of them as a background character. “The girlfriend chorus was kept very busy. It interpreted, comforted, soothed, exhorted and indicated new directions of travel. She had to break free, it said, and she repeated: I’ve got to break free from this idiocy.”

As I read Willful Disregard, my reactions ranged from cringing and shaking my head in disbelief, to laughing and nodding my head in agreement — all in recognition of its essential truth.

Karate Chop: Stories by Dorthe Nors

Translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken

Graywolf Press, 2014

Dorthe Nors’s Karate Chop is one of the few books that truly deserves to be described with that overused adjective, “unique.” The Danish novelist’s first collection of stories is a short, sharp shock that hits you like, well, a karate chop to the neck. In fifteen stories that run from three to eight pages, Nors examines key moments in the lives of her quirky, very human characters as they struggle to make sense of other people in their surreal world. She gets right to the central conflict, stripping everything else away. It’s probably cliché to say, but there is a palpable Scandinavian coolness and efficiency to her stories. Her prose is crisp and economical, with nary a word out of place. She has polished these diamonds to an icy sparkle.

The best stories are glimpses into strange lives or at least strange moments that lead to unexpected results. “The Buddhist” follows a corporate type as he climbs the ladder to the top, where things don’t go quite as he planned. The narrative voice is so cynical and knowing, so droll, that what might be a dull and predictable series of incidents in the hands of a less talented author is instead taut and suspenseful. In “Female Killers,” a husband feeds his addiction to weird websites. “Mutual Destruction” examines the relationship of two friends, Henrik and Morton, who hunt together and have agreed to shoot each other’s dogs when the time comes to put them down. But Morton’s wife Tina has left him, and there is clearly something amiss as Henrik watches Morton and his dog from just inside a stand of trees on a hill above Morton’s property.

The title story is one of the most powerful and haunting stories you are ever likely to encounter and should be widely anthologized. Annelise, a school psychologist, is dating Karl Erik, the father of a young boy she counsels. He told her when they met that “he had a temper, was something of a coward, and a poor father to boot,” but “she never believed what these men said about themselves. Mostly, she had considered this self-deprecation, if not a form of politeness.” But Karl Erik had not lied to her. Pressures and misunderstandings in their relationship had reached a head, and she had applied a metaphorical karate chop to the problem. The ramifications of her course of action remain unmentioned, and the last paragraphs reverberate in the reader’s mind.

These concise, elegant, and disturbing stories require (and reward) rereading. This slim volume packs quite a punch.